Zoon

Published:

Reproducible science and ZOÖN Internship.

Reproducibility in science (without getting into semantics) is the ability of other scientists to reproduce your results. The first step of that is being able to check what you have done. Did you make a mistake with your algebra? Does running the same experiment give wildly different results? As the use of computational methods in ecology increases, we are in a position where we should be able to quickly and easily reproduce the research in an entire paper. First I rerun your code, and check that the outputs match those in your paper (should be easy). Then I check the code for errors (less easy).

However, even the first step is often hampered. Code is not included in a paper, or is hidden in an unsuitable format in the supplementary material, which is hosted neither carefully nor with longevity in mind. When code is included, the data needed to run an analysis is often not. Other times, a script is included, but is a mess with different bits of analysis and output all jumbled together.

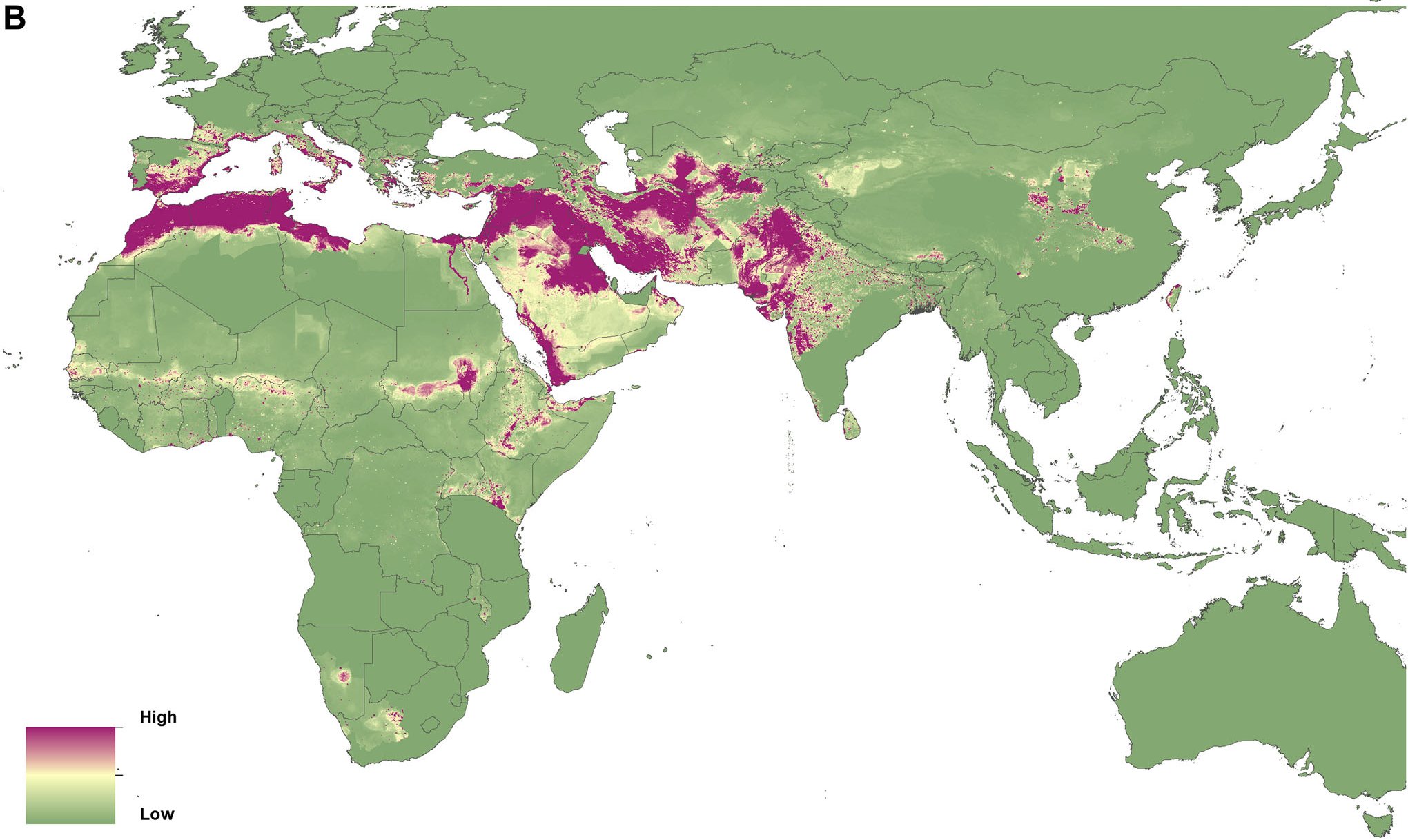

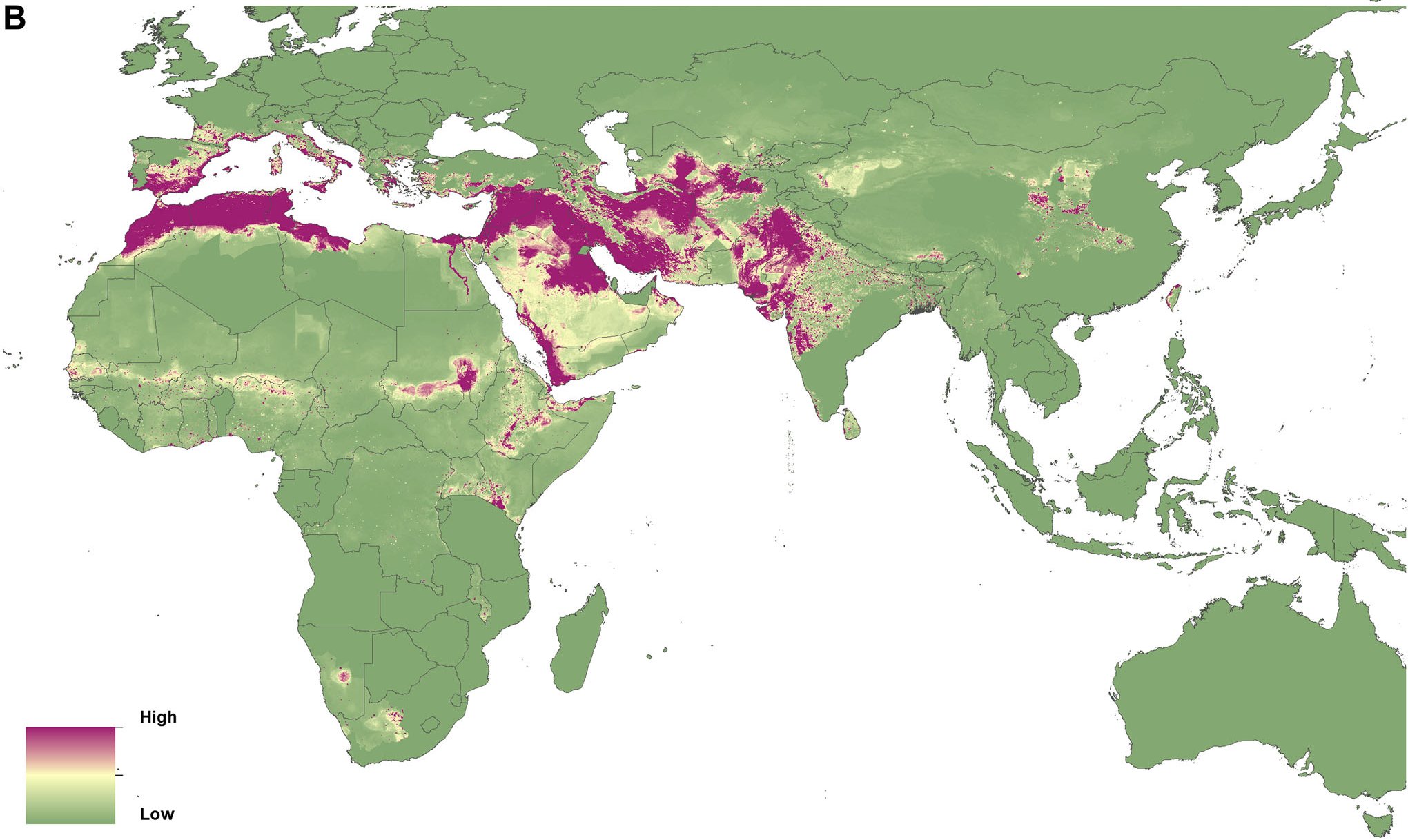

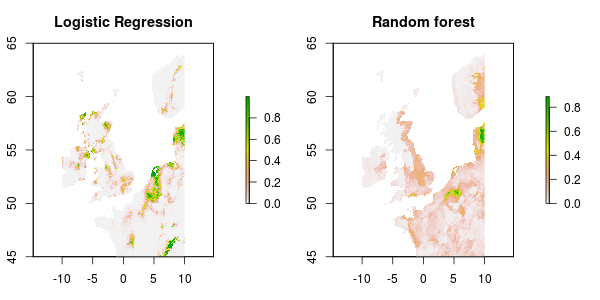

Species distribution modelling (SDM) uses data on where a species lives to predict the whole distribution of the species. In short, a species is likely to exist in areas with environmental conditions similar to those we have seen it in before. So, as long as your data is shared, I should be able to reproduce your results with minimal effort. However, even field defining papers are completely unreplicable. For example Elith et al. (2006) benchmarks how good a number of different models are and has been cited some 3,000 times. However the paper is totally unreplicable. It would be great would be to add more recently developed methods to this benchmark. If a new method can’t outperform the current ones, then it is not very useful. But with the previous benchmark being unreplicable, this is not possible.

The Internship

Over the past months I have been working on an internship creating an R package for reproducible SDMs. The package is called ZOÖN and can be found on github with more information here. The ideas behind ZOÖN have been developed over the last year, with consultation of SDM users at every step (i.e. before I started). It is hoped that this constant discussion will avoid pitfalls of writing software that is then never used. It was decided that while there are great SDM packages out there (biomod2, maxent etc.) there was still a gap for a higher level package, that aids the running, sharing and reproducing of whole SDM analyses, including data collection, data cleaning and outputs. However, as this is a fast moving field, an inflexible package, written and maintained by a small group of developers, would quickly become out of date. So instead the plan is to use web-hosted ‘modules’ that are quick and easy to program (compared to a full R package). ZOÖN will pull these modules from the web and run an analysis. This also means wrappers for other packages can easily be written.

The goal of the internship was to write a working prototype R package which I think I have succeeded in. The working package is on github and can be installed in R with devtools::install_github("zoonproject/zoon"). Although there is some work to be done, the core package works. Whole SDM workflows can be run with one command. The output then contains all the data needed to run the analysis and a record of the call (the inputted text command) used to run the analysis. As the modules are all online, an analysis can be rerun simply be having access to this output (one R object.) In the case of analyses using online data (from GBIF for example) only the call is needed to rerun an analysis. Furthermore, while still in early development, there is already a very simple way to upload an analysis to Figshare.

To run a SDM with the package you must specify at least five ‘modules’. One each that: collects occurrence data, collects environmental data, processes the data, runs a model, gives some output. To flesh out the variety of analyses possible will require much more work writing modules (there are plans for a hackathon to get this going.) However, as wrapping existing packages is easy, there are already modules for running all the models available in Biomod2, collecting data from GBIF, worldclim and NCEP and creating basic maps and uploading analyses to Figshare to name a few.

So in three months I think I have laid the ground work for a package that really simplifies sharing analyses while making it easy for new methods to be incorporated into current analyses.

Open science

This project has been conducted in a very open manner which I have really enjoyed. The code can be found on github as soon as it is written. And the code is licensed to make it useable by anyone. Most of us are on twitter and happy to discuss the research. And as discussed above, regular contact with a user panel means we are not locked in our dark computer lab, working in isolation.

Lessons

Through this internship I have learned an awful lot about the nuts and bolts of R. Writing a package is a really good way to get to know the language better. I can totally recommend R packages and Advanced R for more information.

I have also become much more comfortable with handling a large (ish) software project. Git is now second nature, using Github to record issues has become an invaluable tool and the benefits of unit testing have become clearer.

On a less tangible front it has been really interesting to see how differently people approach approach the community side of software development. Without users, your software is worthless. This project relies on it’s community for more than just a user base. We are hoping for users to contribute code in the form of modules. So community development has been important from the beginning. However I really liked working while talking to potential end users (although a workshop six weeks into a project is terrifying.) I don’t think this approach is easy, but I definitely think it’s worth putting effort into building a community around your software.

And now it just remains to see how the project develops and whether the software becomes commonly used.